Stitching the future: How one fashion teacher is weaving AI into education in Japan

When Naoki Takata first started teaching fashion engineering, being part of a digital revolution in Japanese schools was the last thing on his mind.

Despite majoring in Electronics, Information and Communication Engineering, Takata was assigned to teach fashion at Izuo Technical High School because there was a shortage of teachers. “I didn’t have a fashion background,” he says. “But I studied, and now I’m here.”

Today, Takata is part of a growing group of teachers in Osaka who have completed the mirAI for Japan program and are now rethinking how AI can support both students and teachers. He not only empowers his students to use AI tools to improve their design processes, but also teaches them to think critically and creatively in an increasingly AI-dominated world.

“In our class, we use various AI tools to help students visualize their ideas,” Takata explains. “We’re not just creating images—we’re learning how to use tools that the fashion industry is already adopting.”

A humble pioneer

Takata, who has taught at Izuo Technical for over a decade, is far from the stereotypical tech evangelist. Soft-spoken and self-effacing, he often downplays his role in introducing AI education at his school. But those who work with him see things differently.

“Mr. Takata is very humble,” says Yuri Koura, Head of AI Education at CLACK, the nonprofit organization that developed the mirAI for Japan program in collaboration with Microsoft and has delivered it for teachers across Japan. “He says he didn’t do anything special, but he was one of the first teachers to adopt the mirAI for Japan program and share what he learned with others.”

After completing the mirAI for Japan training, Takata began incorporating image generation AI into his fashion classes, using it to help students ideate designs or create slides for their presentations. He also taught video editing with AI-powered tools, which dramatically cut down the time needed to prepare materials for fashion shows or class projects.

But he didn’t stop there. Realizing that many teachers at his school knew little about AI—and some were hesitant to use it—Takata began organizing open lectures and discussions. He helped the school secure parental consent to allow students to use AI tools in school, as required by many such tools. He also created feedback forms, shared his lesson materials, and even published a paper on the challenges of fostering information literacy and ethics through generative AI, particularly from a design perspective.

“At first, parents didn’t really understand what AI was or why students should use it,” he says. “But we explained the risks and benefits, and now we’re seeing more departments open up to the idea.”

A program for the future

Launched in late 2023, mirAI for Japan was born out of a growing concern: Japanese high school students were using AI tools—particularly generative AI—without understanding the implications. Some were unknowingly violating copyright through images they generated; others were submitting AI-generated text that included misinformation or hallucinations. Teachers, already overworked and overwhelmed, struggled to keep up.

“We wanted to change that,” says Koura, herself a high school teacher before joining CLACK. “Most of the teachers we meet through mirAI for Japan don’t have a background in AI at all. They’re astonished when they realize how AI can make their work more efficient—from generating lesson plans and rubrics to creating practice questions. And they’re often shocked at how quickly students are already using these tools, sometimes irresponsibly.”

CLACK training materials are designed to be as practical and ready-to-use as possible. Teachers receive lesson plans, worksheets, and sample parental consent forms for students to use AI tools in the classroom. “We didn’t want it to be just input,” says Koura. “We wanted teachers to walk away ready to teach.”

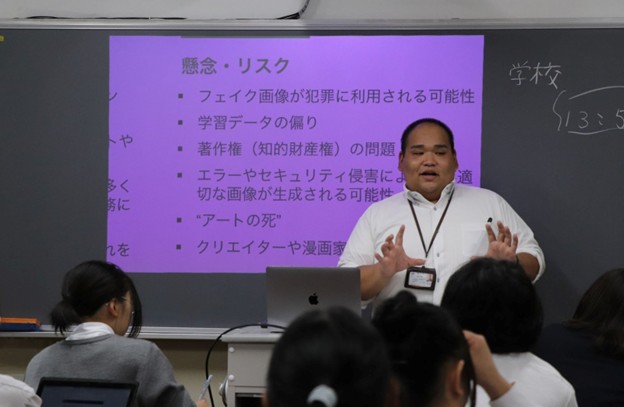

Takata now teaches students to identify biased or incorrect information, and how to fact-check AI-generated content. Before introducing tools like large language models or image generation models, he often starts by discussing their limitations and risks.

“I wanted them to understand the system before using it,” he says. “We talk about copyright, data sources, and ethics. Then we start experimenting.”

The mirAI for Japan program is part of Microsoft’s broader community upskilling initiatives across the country. While mirAI for Japan delivers AI training nationwide, a parallel program called IT Bridge Osaka brings foundational digital skills to high school students in the surrounding region—a growing effort that began with trial sessions at Takata’s school earlier this year. The program introduces students to core topics such as AI, datacenter infrastructure, and cybersecurity, helping them not just to use digital tools, but to understand and support the technologies that power them.

AI as a co-pilot, not shortcut

Despite embracing AI in his teaching, Takata is careful not to let students rely on it too much and too soon. He believes in building foundational skills—in drawing, design, and critical thinking—before turning to AI tools for support.

“In fashion, there are two important abilities: the power to imagine, and the power to express,” he explains. “AI can help with expression, but imagination has to come from within.”

He encourages students to use AI as a co-pilot, rather than a replacement for their creativity. In his fashion engineering classes, students brainstorm and sketch ideas first, then use AI tools to enhance or visualize their concepts. This balanced approach helps them become not only better designers, but more thoughtful users of technology.

And the impact is spreading. After running AI workshops, Takata noticed students outside the fashion department—even those who had little interest in computers—becoming more curious. Some joined IT clubs, others took part in art projects using AI tools.

“That’s the most rewarding part,” he says. “Not just teaching a subject, but awakening curiosity.”

From early adopter to leader

Takata’s efforts have made Izuo Technical High School a model for other schools in Osaka and beyond. CLACK often uses his experience as a case study in teacher workshops.

“Mr. Takata was the first teacher to pilot our student-facing IT sessions too,” says Koura. “He’s always willing to try something new. That makes a huge difference.”

Still, Takata remains characteristically modest about his accomplishments.

“I just thought I should learn about AI, because it’s everywhere now,” he says. “In work, in hobbies, even just watching videos online—AI is part of everything. I felt like I had to catch up.”

Thanks to mirAI for Japan, and educators like Naoki Takata, Japanese classrooms are beginning to do just that—not only catching up with the digital future but also helping to shape it.